By Dr. Gary L. Deel, Ph.D., J.D.

Faculty Director, School of Business

This is the last article in a 12-part series, adapted from my dissertation work at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, on the discord between academe and industry over the role of hospitality education and the purpose it serves in career development for hospitality professionals.

In the previous parts of this series, we looked at 1) the particular characteristics of hospitality education, including a number of controversies concerning its efficacy; 2) the different ways that individuals might value education as a factor in career success; and 3) the way in which such values might be transferred from one person to another in a social context.

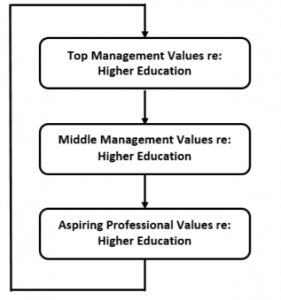

The Recycling of Values Model

In applying existing work to the context of this research, this article series proposed the “recycling of values” model:

A hypothetical example serves to demonstrate this potential phenomenon. As discussed earlier, SLT serves an important purpose in addressing the source of the values of top managers. If values are derived from observation and experience, then it would stand to reason that top managers derive their own values from their experiences in their own careers leading up to their ascension to top management.

How Values Pertain to the Importance of Hospitality Higher Education

The subject of this article series is, of course, values as they pertain to the importance of hospitality higher education. So let us imagine an aspiring hospitality professional with dreams of becoming an industry leader someday. Our professional might have any level of higher education or none at all, but for the purposes of this thought experiment, let us say he holds a bachelor’s degree in hospitality management.

Our professional might first find himself working in an entry-level role, such as front desk agent for a hotel company, to gain necessary experience. After six months or so, he expresses an interest in a supervisory position with his company. When he consults with his direct supervisor, the front desk manager (a middle manager in this organization) he is told that “college doesn’t teach skills necessary for supervisory positions” and that he should have at least one year of experience as an agent before applying.

Our professional waits until he has met the experience requirement, applies for the job and is promoted. He finds himself using some of the knowledge and skills that he learned in college, but he concludes that most of the tasks he is required to perform, he could have learned and mastered with or without his degree.

After a few more years, he sets his sights on an upper management role. He thinks he might need a graduate degree in order to be considered, but when he checks the job description, he finds no mention of a formal education requirement.

He also researches the profiles of some of the company executives that he aspires to emulate someday. He finds that few, if any of them, have any college education to speak of. Finally, he approaches the general manager (GM), who is himself a college dropout, and is told that “all that theoretical mumbo-jumbo isn’t going to help you run a hotel.”

According to this successful GM who lacks a college degree, all our professional needs to do is “work hard.” He takes the advice, forgoes a graduate education and instead focuses on his industry experience. He is rewarded with several promotions until he himself is eventually sitting in the general manager’s office of that very same hotel.

Based on SLT, it would not be surprising to learn that our professional, through the course of his experiences, has developed a belief that higher education is not necessary to success in the hospitality industry. After all, he has a degree, but it wasn’t necessary for any of the professional roles he held along his own career path. Most of the people for whom he has worked in his career lacked college degrees, and they did just fine as well.

To top it all off, he remembers how the general manager he respected very much told him higher education was a waste of time. And he was obviously right — just look at how things turned out. Our professional now sits in the GM’s chair, but in terms of his views toward education, he is indistinguishable from his predecessor.

The next link in this chain of values comes when our professional — now general manager — begins shaping and molding the values of the people who work for him using the values that he learned through his own experiences. Employees who work for our professional’s hotel learn of the circumstances of his success. This next generation of professionals is now applying for their next promotions, and they’re discovering what it does (and does not) take to be successful in this organization.

Some of these employees are even scheduling appointments to see the GM so that they can ask him about their career development, just as he once did with his predecessor. One can imagine what he might tell them about the importance of higher education.

Soon, the cycle completes itself. The employees of the GM’s hotel are the general managers of their own hotels, proliferating their values and developing the next generation of top managers.

Hospitality Careers without Higher Education Are Becoming the Exception

But this is obviously just one potential sequence of events. And while there have been many who have ascended the hospitality career ladder without a college education, this is quickly becoming more and more the exception rather than the rule. Pressure from rapid technologization and enhanced sophistication in business practices is increasingly demanding specialized knowledge, skills, and abilities that were not as pertinent even five or 10 years ago.

What if our professional had been led in a different direction on the value of higher education? What if he had worked in a hotel where his supervisors and leaders were college educated? What if they had recognized and touted the value of hospitality education instead of disparaging it?

In addition, what if he had discovered that there were skills he needed for career progression that higher education could deliver? What if he hit a career ceiling where a graduate degree was required for a promotion because of organizational hiring standards?

The presence of any of these circumstances might have resulted in a perception that higher education in hospitality is indeed important to career success. So this pendulum swings both ways.

Obviously, there are a number of variables in such a hypothetical that one might play with. The fact remains, however, that there is considerable research evidence to suggest that a relationship among the values of top management, middle management, and aspiring professionals might exist such that this “recycling of values” is worthy of further investigation.

Comments are closed.