Podcast with Gary L. Deel, Ph.D., J.D., Faculty Director, School of Business and

Ray Eddy, Professional Stuntman and President, Orlando Stage Combat

For viewers, action sequences add thrills to big blockbuster action movies and other entertainment. But this type of work is typically performed by professionals who have been trained to safely perform such stunts to prevent themselves and cast members from injury.

Start a management degree at American Public University. |

What is it like to be a professional stunt person? In this podcast, Dr. Gary Deel talks to Ray Eddy about his career as a stuntman, the physical training and techniques required to execute certain stunts, and how he maintains focus and control to avoid injury. He also discusses the pros and cons of actors doing their own stunts in films and the role of CGI technology.

Listen to the Episode:

Subscribe to Intellectible

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google Podcasts

Read the Transcript

Dr. Gary Deel: Welcome to the podcast, Intellectible. I’m your host, Dr. Gary Deel. Today, we’re talking about the life of a stunt performer in entertainment.

My guest today is Ray Eddy, who is currently an instructor in the entertainment management program at UCF Rosen College. Before that, Ray started out headed for a technical career, majoring in math and economics at Duke University.

But after working in that world for a little while, he decided to break away and pursue his crazy dream of being a stuntman. He obtained a position at Walt Disney World, playing Indiana Jones in the stunt show there, followed by other stunt roles, a stunt management position, and eventually, he started his own independent film company.

Today, he is a university instructor sharing his entertainment experience with his students and working on a Ph.D. in texts and technology. Ray, welcome to Intellectible, and thank you for being our guest today.

Ray Eddy: Thanks a lot. Great to be here.

Dr. Gary Deel: Absolutely. So I guess to get us started, at what age did you decide you wanted to be a stunt man?

Ray Eddy: To be honest, when I was about five.

Dr. Gary Deel: Really?

Ray Eddy: Yeah, absolutely. Since I was a little kid, I always wanted to do this. I had friends who wanted to be firemen or astronauts or whatever, but I saw something on TV about stuntmen as a child, and I was so enraptured by the entire concept of your job is riding horses and pretending to fight people and jumping off of things and landing on big airbags.

I thought that’d be the coolest thing ever, and always thought I wanted to do that and never thought it was realistic. So to answer your question probably more specifically — when did it become a reality — I was about 25 and I had gone through college and career and graduate school, my master’s degree and then my next career.

At that point, I just sort of said, “It’s time to give it a shot now or else I never will.” That’s when I made the determination to change my career path and try to make it happen.

Dr. Gary Deel: That’s interesting. As a child, did you have any background in sports, or I’m thinking maybe gymnastics or anything that would have lent itself to the work that you do in stunts?

Ray Eddy: I would say gymnastics is your correct and most appropriate one. For stunts, it’s the most helpful one, but no, I actually did not do that.

As a child, I was not super athletic. I liked riding bikes and running around, but I was certainly not known for being a superior athlete. Once I got into high school, I got a little better about that. I ran track and I played in the tennis team, but I was more of a marching band guy than a football guy, if that makes sense.

So I enjoyed physical activity, but I wasn’t exactly an expert at it, I wouldn’t say by any means. But I just always loved doing exciting things. I wouldn’t just ride my bike; I’d set up ramps and jump over the ramp. I wouldn’t just ride my skateboard; I would set up cones and things. I’d be weaving back and forth to make it more exciting.

So that was kind of my approach to activities was to make it maybe one notch more exciting, but I wasn’t the kid who was jumping off the roof because I was crazy and I would break my arm. I wouldn’t consider myself to have been a crazy risk taker, but that’s a whole different aspect of stunt work.

It doesn’t mean you have to be excited about taking an unnecessary risk; it’s just having a controlled risk. So maybe it was a better balance that way.

Dr. Gary Deel: Yeah. The off the roof, onto a trampoline, into a swimming pool and inevitably breaking some number of bones in between.

Ray Eddy: That’s right.

Dr. Gary Deel: We see those on YouTube all the time. So did you ever ride anything with a motor as a kid like dirt bikes or ATVs or go-karts?

Ray Eddy: No. In fact, I could credit my parents for that. I really wanted to have a four-wheeler or a three-wheeler or something, and they were staunchly opposed to that because it wasn’t safe.

And so I did not. I was just pedaling and I’ll make it go. But no, it wasn’t really a big part of it. But not that I didn’t want to, I just didn’t have a chance to.

Dr. Gary Deel: Yeah. Well, I asked because I raced dirt bikes throughout my childhood and I knew a lot of folks that were into what I call the X Games craziness of, can you take a dirt bike and flip it backwards three times in the air and then land it on the wheels? I never had the inkling or desire to do that, because I just saw people splattering themselves all over the ground and it just seemed like a risk not worth taking.

Ray Eddy: That’s definitely a turnoff to most people for their careers, is the potential for catastrophic outcomes. So you’re not alone in that.

Dr. Gary Deel: Yeah. But you know what’s interesting as we’re talking about it, because clearly there are some folks who live and die by that. And I don’t mean literally, although of course stunts and stunt work have claimed lives, but there are people who it seems like they need that in their lives as if it’s an adrenaline rush or if it’s a need to push the boundaries of what’s possible.

I’m thinking about the Travis Pastranas of the world and the people who are just, “How can I get on a motorcycle and do something different? I’ll jump off the Grand Canyon or I’ll jump off a major casino in Las Vegas just to see if I can do it and to get that rush.”

Dr. Gary Deel: For people like me, and I suspect it sounds like you’ve shared a little bit of the sentiment. It seems so risky in light of the consequences that, is that really where you want to risk your life and possibly be your very last day is that day jumping off of a casino in Vegas and hoping you hit the ground in the right place?

Ray Eddy: Right. Right. That’s definitely probably the distinction between being a stunt person and being a daredevil. Those of us in the industry would say, there’s a line of demarcation between those two things.

The Evel Knievels of the world did crazy stuff just to do crazy stuff, people at monster truck rallies who put themselves in a box and let it blow up or jump a limousine over a bunch of school buses. Those are exciting things to watch, and those men and women do that for the excitement and the thrill and the show of just the actual thing that they’re accomplishing.

The difference between that and being a stunt performer is in a stunt performer, you’re trying to make it look realistic as if it were someone else. Or perhaps you’re playing the role yourself and making it look like something really happened but not really happening.

So it’s maybe like more of an acting thing. It’s not like it’s a magic trick because there’re certainly risk involved, but we’re not just doing it purely for the daredevil aspect, which is great too in its own respect, but that’s kind of a different approach to it really. It’s kind of a different way to go after it.

Dr. Gary Deel: Right, absolutely. So your first foray into stunts, if I understand correctly, then was at Walt Disney World. Is that correct?

Ray Eddy: The first time I was making a living at it. Sure, yeah.

Dr. Gary Deel: Okay.

Ray Eddy: When I was 25, as I said, I jumped into it. I lived in North Carolina at the time and I just decided I want to do this crazy thing, and so I started off. Honestly, one of the first thing I did, what you referred to earlier, is I started taking private lessons in gymnastics just to get better. I was fit. I would consider myself to have been somewhat of an athlete.

Again, I was never like the best. I wasn’t the star on the football team, like I said, but I worked out a lot and ate right. And so I was in shape, but I didn’t have the body control that I needed.

So gymnastics was a big part of that, so [I] did that for quite a while. I took martial arts training and I took some training in stage combat, which is pretend fighting, some acting lessons, and then I met some stunt people in Wilmington, North Carolina, which is where there used to be a major hub of film.

There’s still some filming done there, but it used to be the third biggest city in the country as far as production. After Los Angeles, New York, it was Wilmington.

That is no longer the case, but at the time there were lots of people and I met some stunt people there and started training with them. And they taught me how to do high falls and fire burns and how camera angles worked and learned about some car stuff, how to slide a car around the corner, and it got real stunt.

That’s where I knew I was in the right place. I could just feel this was happening.

We did some charity events, some fundraisers for different organizations. I did little things here and there. I was like in a commercial and an independent film where you don’t get paid. Your pay is they’ll feed you and you’re learning and you get a credit on your resume, and at the time, a copy of it on a video cassette, a VHS tape.

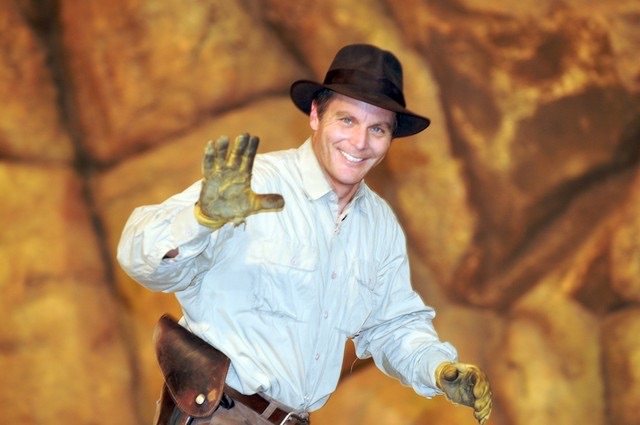

But then when I auditioned for the Indiana Jones show and got it, that was the first actual legitimate, I would say, for sure, legitimate work I was doing in stunts, for sure.

Dr. Gary Deel: Gotcha. Now you mentioned that going in, you didn’t have the “body control.” When you say that, are you referring to flexibility or hand-eye coordination, or is it something different entirely, all the above?

Ray Eddy: The term I would use for it, if you want to get a little scientific, it’s called aerial kinesthetics.

Dr. Gary Deel: Okay.

Ray Eddy: It’s being able to feel where you are when you’re upside down. So if you’re coming down to the ground, are you going to land on your back, or are you going to land on your neck, or are you going to be landing on your feet? So that’s a body sense in the air that gymnasts are obviously very good at. Same with divers, people who dive swimming, top divers, are very good with that aerial sense.

And so if you’re going to do high falls, you have to not only know where you are in the air, but to be able to control that as much as you can. There are ways you can wrench your body and twist things around to make yourself move in the air to land safely, which is a really big part of high falls, which is a big part of stunts. And then just generally, better body control.

I don’t think I was uncoordinated, but it gave me a much better sense of where my body was as I was moving through space. I would say that’s the best way to look at what gymnastics did for me.

Dr. Gary Deel: Seems like a sense of orientation, if I understand you correctly.

Ray Eddy: I think I’d also say, so if I can add on, I was never going to be a college gymnast. Those people are phenomenal athletes, they can do anything.

I’ll be honest, I could do a round-off, back handspring, back tuck. If you know gymnastics at all, that’s pretty basic. It’s not just a somersault, but I was not doing double fulls and layouts and really complicated things that superior athletes could really do.

But if I could do, to me, if I could get to a round-off, back handspring, back tuck, now I know I can get myself through the air safely and do something somewhat physical that might be helpful in the future. That’s the point where I got myself with my private training.

Dr. Gary Deel: Got it. So when you got to Disney and you were offered the position, were the requirements of Indiana Jones well within your wheelhouse at the time, or was that something that was a major step up from anything you had done previously?

Ray Eddy: Fortunately, with the training I’d been doing, it did kind of line up with that. The biggest part of that character that will get you even in the door at all is you have to resemble Harrison Ford when he was between 20 and 30 years old-ish. That’s kind of what they went for, around the 25- to 30-year-old range.

So it’s a kind of typecasting that is legal, but you have to be Caucasian. And it helps if you have brown hair, but that wasn’t mandatory, be of certain physical appearance and a certain height, and I was lucky enough to hit all those marks. That was a part I got lucky with.

The requirements for the audition said that you had to be comfortable with heights, so I had that. And it helped if you had a physical background, if you had any experience with rock climbing, just to know you could get yourself down a rope because there’s some rappelling in that show and just physical capabilities. And so the audition itself involved all those.

The process involves, first, a type out, the physical look, and then a strength test, and then an agility test. So the strength test is pull-ups and the agility test is a dive roll and a shoulder roll and just basic gymnastics.

But if you can do a round-off, back handspring, back tuck, you can do a forward roll and look like you have body control. That’s kind of where that came from.

A really basic stage combat sequence, throw a couple punches, duck and block and real easy stuff just to make sure you could not only control yourself and throw a punch accurately and safely, but also take feedback from the trainers. If they say you’re throwing it wrong, do it like this, and you can’t change, then it’s tough to train someone who is so ingrained in a certain system, so the ability to be flexible and learn as you go and modify your technique.

So it’s a little bit of everything. And then at the very end, if you get to the very end of the audition process, they gave you some lines and they have you read some lines on a camera. If you can enunciate clearly and project and have a personality, then that helps too. So, all these little check boxes.

Now, I’ll say I did not get it the first time I auditioned, for sure. It took me several tries to get it, and I got better every time at what they were looking for. So that helped as well. I didn’t walk right into it, for sure.

Dr. Gary Deel: It’s been a long time since I’ve seen the show. But you just mentioned speaking lines and I know that some shows are prerecorded scripting of audio, and so you just kind of pantomime the words and it’s just the same every time. Do I understand you correctly in saying that there’s actual speaking from the Indy character that the actor does?

Ray Eddy: Yes.

Dr. Gary Deel: Okay.

Ray Eddy: But without going into the whole show, it recreates three scenes from the movie “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” The opening scene of the film when he gets the golden idol with all the traps in the cave, a scene running around in Cairo with bad guys chasing him. He fights them off with a whip, and there’s explosions and rope swings and teeter boards and all kinds of stunt action things going on around.

And then the last one is the scene where he fights the big muscle-bound guy with an airplane spinning around. So they have an actual airplane-ish. It’s a mock airplane that comes out and spins around on the set and while you’re fighting around it. So it’s those three scenes.

Ray Eddy: So during the scenes, the lines are basically “Look out!” and “Duck!” and “What are you doing?” Or “Oof!” because you get punched. So not really a whole lot of conversation going on because it’s just not necessary and relevant.

But in between the scenes, we have these interstitial sections where they’re resetting the set for the next scene. We have to fill time for the audience.

During that time, we’ll have a conversation about what stunts are going on or how you do it. It’s just basic filler. You’re not putting on a Shakespearean monologue, but you have to give about a paragraph of text and look natural with it, and that’s about it.

Dr. Gary Deel: Sure. You just reminded me of something, and this is off-topic. But have you ever seen the documentary of the three friends that filmed an amateur scene-for-scene reenactment of “Raiders of the Lost Ark” with the airplane scene and everything? I think it was on Netflix.

I don’t know if you’ve seen it or not, but it was really an interesting story how they had spent most of their teenage years trying….they were just in love with this movie and they had filmed every scene angle-for-angle as it had been done. But they had been missing the plane scene because of course they didn’t have the budget to do like this massive scene with a realistic World War II plane, and so on and so forth. But it was a really cool piece that they had worked out, and I think they had actual stunt people.

Ray Eddy: Yeah, I did see that. In fact, there was a documentary about the making of that that I saw at a film festival.

Dr. Gary Deel: That’s where I think I saw it as well, yeah.

Ray Eddy: Yeah. It’s just fantastic because they did it when they were kids with no money and no safety. They set a guy on fire. He’s okay, but pure luck that no one got killed. They made the boulder scene in their backyard.

It’s adorable and hilarious and fantastic. I just love it. They did it over the course of years. They go from being a kid to a teenager to an adult from scene to scene, because it’s the same people as actors for the entire thing.

And so by the time they get to that airplane scene, you’re right, they’re full-on adults. And they finally got the money to go out shoot that one last scene and they did it, and it was just very emotional. It was a beautiful undertaking. I’m a big fan of what they did.

Dr. Gary Deel: Yeah. Now I thought it was interesting, too. So you mentioned heights and high falls. So what kind of heights are you talking about in Indiana Jones? And once you learn how to do something like that, does it matter how high you’re falling from? I mean, can you jump off of a much higher building with the same level of confidence?

Because these are things that I’ve never done, so they’re very alien to me and I imagine to many of our listeners. So I guess the question is, is it like flying an airplane where you could fly at 30,000 feet or at 30 feet and it’s still flying?

Ray Eddy: I would say generally the answer to that question is no, because it’s pretty different. The technique is essentially the same. There are some things that happen when you’re falling for two seconds versus 15 seconds because your body will keep on rotating.

And if you don’t jump the right way, if they’re a little bit off on a really high fall, then you’re going to miss that pad by 10 feet and you can die. If you’re falling from 20 feet, you’ve got a much better chance of hitting your target and landing safely. But beyond that, honestly that really comes down to how comfortable you are with heights.

So to answer your question on Indiana Jones, the first thing is, well, I don’t want to give the whole show away, but there’s a 60-foot drop, but you don’t hit the ground. There’s a safety mechanism that catches you before you hit the ground.

And then later on, there’s, I believe it’s about a 25- to 30-foot high fall that Indy does off the top of a building onto, really, it’s just a big, like a gymnastics pad that they use for track. Like if you’re doing the pole vault and you land on that big squishy thing, that’s the kind of pad they use.

It’s hidden behind a clothes rack on the set, so you don’t see Indy land. The joke is he’s landing in a pile of clothing because clothing shoots up in the air when he hits the ground.

Dr. Gary Deel: Gotcha.

Ray Eddy: So that’s about a 30-foot-high fall under that one. That’s [a] pretty reasonable amount of height, but you work your way up to that when you train. You’ll start off on a trampoline. So you just jump up in the air, and then can you twist in the air and land safely on your back? Can you flip over forward and land on your back? Can you go backwards and land on your back? Different types of high falls.

If you’re good with the trampoline, then you move up to like an eight-foot fall. If you can do that safely and consistently, you go to a 13-foot fall, then you go up to a 21-foot. So they find different places where you can train and just work yourself up to that level of the biggest one they have, which is about 30, then you’re good to go. That can take a day or it can take weeks before you get comfortable at every level, and you’re safe and consistent.

And then I went over to another show at Disney, it was called “Lights, Motors, Action.” It was mainly a car and motorcycle stunt show, but it’s no longer there.

Unfortunately, it’s not in the park. It got replaced by the new Star Wars area, the Galaxy’s Edge. In that show, I was able to play a different character, the stunt coordinator who played a villain in one scene.

And we did closer to like a 50-foot-high fall off of a building there, same kind of landing pad. I’ll admit, the first time I did it, it’s much different. Where 30 feet to 50 feet you don’t think it’s much of a difference, but it sure is. Another second or two falling, you’re sure to catch your breath. After you do it a few times, you kind of get used to it.

But I think what it really comes down to — to really answer your question — is I’ve always felt that if I ever felt really comfortable and relaxed and casual doing a high fall, then I’m probably not taking it seriously enough and I’ll start relaxing too much and not focus.

And then I might land badly and I can really get hurt. Even landing on a high fall pad or airbag correctly is okay. If you land incorrectly on a safe surface, you can still get seriously hurt. So it’s really a lot about focus and control and having comfort with those heights.

Dr. Gary Deel: Yeah. So I was going to ask then what are the common types of injuries, and is that usually the causes? People just getting careless about the way that they approach their jumps or their falls or what have you, or is it something else entirely?

Ray Eddy: My experience would be, it’s never been about carelessness. There are injuries, but it’s usually freak circumstance. It’s something crazy went wrong that couldn’t be predicted or mechanical failure.

I can’t recall a time when I saw someone get hurt because they were being stupid. It’s usually a tragic sequence of events that just everything went wrong in such a weird way that no one predicted.

And the end result was someone got hurt or tragically seriously hurt or even killed, and that has happened. There have been a couple real serious ones that are really just hard to even talk about, honestly, but it was never for a lack of concentration. It was just something weird happening.

I’ll just give you one example — one of the ones that happened to me. Thankfully, I wasn’t too badly hurt, but I couldn’t finish the show. When that airplane is spinning around, there’s a part where I go backwards underneath it the very first move I do, and three things went wrong.

The placement of the plane was a little bit funny. It got parked a little bit weird. The place that the actor and I were standing was a bit funny. And so I was going through it at a different angle just by a little bit, and the character who makes the plane start moving triggered it just a fraction of a second early.

Those three things going wrong, my head hit a bolt sticking out the side of the motor that drives the engine. I had to get eight staples in the back of my head, because it cut my head open and it was bleeding badly. I don’t mean to be graphic. I was never unconscious, but I couldn’t stand up, and they had to stop the show because I was rolling around the ground, waving my arms, like I was trying to stand up and couldn’t find where the ground was.

Once the other actor realized that, he stopped the show. We have an emergency cut signal, and they just stopped the show and called the emergency services and got me off there and stitched me back up again. But again, that was three things had to go wrong for that to happen.

That’s just one example of 100 I could give you. I could fill up the rest of this hour with stories of people getting hurt, which is really unfortunate. But I hope that kind of makes the point that it takes things going wrong, typically things going wrong tragically, for someone to get hurt in stunts.

Dr. Gary Deel: Definitely. I appreciate that. I can imagine it’s unfortunate every time it happens, of course, but are there some injuries that are more common than others when it comes to like muscle pulls or tendons and things versus in your case. I mean, you hit your head and it was [a] complete accident, but it took that weird confluence of different circumstances to make that happen. But are the kinds of things where you talk to the average stuntman and they’re going to tell you, “Yeah, I’ve definitely done this three or four times in my life because that just goes with the territory”?

Ray Eddy: There are a couple of different things. I may need to explain one other thing too. There are two different kinds of approaches to a career in stunts. And what I’m really talking about today is stunts at a theme park, because the other part of it is doing stunts in movies and television, which is a whole different animal.

A lot of those are one-off stunts. I mean, you’ll do a giant high fall or you have this crazy fight scene in a bar or something really ornate and complex. You’re driving a car, jumping from a car, a limousine, jumping from the top of a semi onto a side road, whatever. You’re never going to do that more than one time.

I mean, you might have to do two or three takes to get it right, but once that scene is done, you’ll never do it again. Because of the danger and the risk and honestly the money involved, they tend to have sometimes large-scale catastrophic things can happen if things go wrong.

In a stunt show, because it’s going to happen, the Indiana Jones show when I was doing it, it was five times a day. I might be in it maybe just two or three shows a day necessarily, but some characters would maybe do five shows in a day and five days a week.

Maybe over the course of a week, you do a few five show days and some three show days or whatever. That much pounding on your body, it had to be controlled and safe enough within a range of safety that there wasn’t a high enough risk that someone could potentially get hurt without a freak circumstance.

So what that led to then, frequently, it wasn’t the one-off crazy accidents of me getting a concussion in the middle of the tarmac out there. It was more like it’s the constant pounding of your body.

So it’s the tumblers who were chasing Indiana Jones around are tumbling. They’re doing big tumbling passes over and over, and they’re just pounding their knees and their ankles and their backs and their necks. And so just day after day after day. You have to be a superior athlete to maintain that over time.

So a lot of times, for some characters, it was more their back or their knees, like you said, pulled muscles or tendons, and then sometimes it’s just the one off freak, crazy thing where somehow you stepped off the side because it was slippery or something distracted you and you sprained your ankle because you stepped on something wrong. And then you’re out of [the] show for a few weeks because you have to get healed back up again.

I wish there were one answer of what’s the most common injury, but it’s such a varied thing that there’s so many things that can happen.

Dr. Gary Deel: Yeah.

Ray Eddy: I’m not sure which one’s the most common injury to have.

Dr. Gary Deel: Now you mentioned stunts in film. I’m curious to know, because I know you said they’re entirely different animals. Are the skill sets at least comparable? And is that something that you ever had aspirations for in your career to transition to like a film stunt role, or were you more interested in the theme park side? Is that just how fate worked out for you?

Ray Eddy: My original dream was to — at the time — was to go to Hollywood and try to do stunts in movies, for sure. I think that’s kind of the big time. Working in a theme park is great, but working in movies it’s almost like the major leagues versus the minor leagues, in some ways.

The difference is working in stunts — if you’re going to be out in Hollywood — is you might work on a film for a month or so and then you might have no work for six months, because it’s all about hustling in the next job. A big part of your job when you’re working in stunts or in acting most anything in Hollywood is finding your next job. So if you don’t have another job lined up, you might work for a while, and then you might have a real downtime.

The difference with that with working in a theme park is you have a full-time job. I mean, as long as the show keeps on going, and as long as you keep your contract, you have a five days a week, 52 weeks a year minus vacation. You’re working and you have a paycheck and you have benefits, and it’s consistency and stability.

So there’s certainly an appeal to that, knowing that you have work constantly as opposed to having to hustle for work constantly. But I think the biggest thing that switched it for me when I got to Indiana Jones and did it for a few years, was that several of my friends at that show were in the process of moving out there.

And they moved out to L.A. to try to make it, and then so many of them came back just saying, “It’s terrible. It’s hard. It’s crowded. Does not have work for everybody. And if you don’t know the right people, you’ll never get work. It’s frustrating.”

And they just forget it; they come back and they say, “It’s miserable out there.” And they came back to Orlando and got back into stunt show at Disney World.

But then there are some who made it. And there are certainly some people out there from the Indiana Jones show who have made fantastic, wildly successful careers as stunt performers out in Hollywood.

Some actually come back to Orlando every now and then and keep on doing the show just because it’s still fun, but they don’t have to. They just do because they can.

I would say the proportion of people who have gone out there and have hated it and have been miserable, kind of convinced me. I was like, “I like doing stunts all the time, and I love this character, and I love this show. I think I might just hang out here.”

I tried to convince myself it’s not that I bailed out or gave up on a dream, it’s more that I just really found out I loved what I did. I was so happy and I got to do other things outside of it that led to other careers and other opportunities that I could make my own work.

That’s what convinced me. I was like, “I’m happy here and I got some stability. We’ll see how this goes.” I’ve actually been very happy with that decision.

Dr. Gary Deel: It sounds great. It certainly sounds competitive. I know we have a mutual friend that we didn’t know about until we discussed, but someone that worked with you at the Indiana Jones show and was my kung fu instructor for a number of years who I remember seeing him in several movies, little parts here and there, but I know that that was an ambition of his as well. So I can imagine it’s a real challenge to cut your place in that career niche.

Ray Eddy: Yeah. Yeah. He was in “Ant Man,” I think. Was that one of the first ones he did?

Dr. Gary Deel: I believe… I want to say “Green Lantern” too, if I’m not mistaken.

Ray Eddy: “Green Lantern,” yes. He did superhero stuff, but yeah. He’s a great guy, super talented. So yeah, you’re right.

Dr. Gary Deel: Absolutely, yeah. He took me to a gymnastics gym once. I tried my hand at somersaults, and that was about it.

We were talking about some stunt performers who make their way to Hollywood, and I’m just curious if you have an opinion on actors who do their own stunts, because we hear about this all the time.

For some reason, Tom Cruise keeps coming back into my head. In the “Mission Impossible” series, I had read that he broke his ankle on a jump in the last one from one building to another. And I always think to myself like, “Why don’t you just have somebody do that for you?”

So when you hear about that, do you get the same thought, or is there a certain amount of satisfaction that comes with acting and doing your own stunts? It seems like it’s almost like a personal pride issue for those in the performing arts.

Ray Eddy: There are a lot of different ways to approach that. First, I will say this about Tom Cruise. He does a ton of his own stunts, and he does amazing work. I think I saw somewhere he’s so dedicated to how well he approaches these things that he does months of training to get good at certain skills.

There was something he did underwater where I think he burst a blood vessel in his own eye, because he held his breath for so long. It’s just ridiculous. You don’t have to do that, but he just dedicated himself.

And yeah, the injuries that he sustained — this is actually pulling a line right from the Indiana Jones stunt show — the reason why they technically shouldn’t do that is because if they do get catastrophically hurt, then the whole film shuts down. They can’t do the movie without the lead actor or actress, so they shouldn’t do things that are so dangerous that they could end the production.

That’s not me just saying that. That’s just a general industry standard. So we’re trying to make sure that production will continue and everyone has a job, not just the actor who…It could be because they want realism. It could be because they want to do it because it looks like it’s fun.

So in that respect and as a stunt performer, I’ve done some acting as well. But I consider myself a stunt guy too, we actually would prefer that they not do their own stunts because it’ll give us more work. So just right off the bat, let’s give everybody a chance to get more employment.

But sometimes if something is a real closeup and you can really see someone’s face — that technology exists — you can digitally put someone else’s face on your body. They’ve done that in obviously lots of movies like “Count Dooku” with his lightsaber, fighting in some of the early episodes of “Star Wars”, that actor, it was… Was that Christopher Plummer, get the right person? They had someone else doing the sword fighting and they digitally put his face on that actor.

So that can happen now, but it requires a lot of money and time of digital CGI effects. So you can save the money and the camera angle of getting it right with the actor doing their own stunt. But once it becomes dangerous, if you’re on a motorcycle and you wipe out and you break your neck, then that’s it. The movie is over, and your career obviously might never be the same and your life might never be the same.

So a trained stunt performer who can really ride a motorcycle in a really dangerous-looking way that’s really as safe as it can be and knows how to fall and slide and not roll and get tangled up and get seriously injured is really better for everybody. So I’m a big fan of… Unless there’s some real technical need in a film for an actor to do their own stunts, I would strongly advocate for them to allow us, a stunt person, to do it just for everyone’s wellbeing, really.

Dr. Gary Deel: Don’t try this at home.

Ray Eddy: Exactly.

Dr. Gary Deel: So you brought up a good point, which makes me wonder with the advancements in CGI that we’ve seen already and the things that I see today. I’m thinking of the most recent installment of the “Fast and Furious” franchise, which was the one where Jason Statham and The Rock partner up against Idris Elba. There’s just some incredible stuff there that clearly never happened, but yet it’s almost indistinguishable from reality at this point because the CGI is so good. So do you think we’ll reach a point where actual stunt work is almost just unneeded, because we can just computer generate anything that seems dangerous or difficult and it will be indistinguishable to the viewer?

Ray Eddy: It’s funny you bring that up, because that’s a conversation that has come up throughout the years of filmmaking. In fact, I would take it back to when animation became more technologically accessible. So it went from the original movies, the black and white, maybe with no sound, and all of a sudden, you have feature animation coming out.

Actors were petrified at that time that actors might never work again. Because animated characters can do anything and they’ll never get hurt and they’ll never go on strike and they’ll never complain. They can do whatever you ask them to do, and they’ll do it happily, and so why do you need an actor? We can have an animated character. That clearly didn’t happen because there’s a demand among the film-going public to see real people.

I think when CG effects have gotten better and better, I think there are certainly some stunts that have become less common. I think there are not nearly as many hugely dangerous high falls as there used to be back in the days of Dar Robinson jumping.

He’s a famous old-time stunt man, jumping off top of a skyscraper and falling the entire length of this… I mean, I don’t think that would ever happen again because it doesn’t need to. You can CG a body falling from a skyscraper without any danger. And things like fire, you can have pretty realistic-looking fire in CGI without setting a person on fire.

But in my opinion, again, there is a real difference between a practical effect and a CG, a computer-generated effect. Until that becomes absolutely indistinguishable, I think there’s always going to be a demand and a need for something practical.

That’s one of the things that came up…I hate to come back to “Star Wars” again, but in some of the more recent “Star Wars” films, they got away from the CG effects and more into actual explosions of real TNT or whatever they used. Actual things blowing up and people doing real fights and filming an actual human being doing things. And you can still tell the difference and it adds a level of realism and humanity to it that I think makes the film better and has more depth and more nuance to it.

There may come a day when that is so good you’ll never do a stunt ever again. I don’t think we’re there yet. I’d like to think we’ll never get there, because there’s something about that real human presence that can’t be digitally recreated. I hope not, anyway.

So I’m currently not in fear that stunts will disappear. If nothing else, right now stunts are probably less expensive than CG effects, because CG is so expensive. Again, that will get cheaper over time too.

We may find some confluence of events where CG is cheap and amazingly realistic, and stunts go away. But I feel like the same with animation and acting, I feel like there’s probably always going to be a need for something in real action stunts, real, practical stunts happening.

Dr. Gary Deel: I think you’re right. I remember reading that about J.J. Abrams’ aim when he was directing “The Force Awakens,” the seventh “Star Wars” movie that the aim was to separate themselves as much as possible from the prequel trilogy with all of the CGI that people were not huge fans of.

I think something else is worth pointing out that it’s my suspicion, at least, that even when the technology reaches a point that it is literally indistinguishable from reality, the realism is so perfect, I think there will still be an authenticity component that people will cling to, traditionalism, In the same way that people still listen to record albums even though we have CDs and MP3s and digital downloads on iTunes. It’s just this feeling of this is more real, or there’s a nostalgia to it almost that I think people long for.

It makes me think about, in appreciation for something that I learned recently, there’s a movie that Chris Hemsworth starred in. It was on Netflix. I’m sure it’s still available there. It’s called “Extraction.”

I don’t know if you’ve seen it or not, but I had learned after watching that movie that it was — and I don’t know the gentleman’s name, so forgive me — but it was actually directed by a former famous stunt person in Hollywood. The scenes in that movie, some of them were just so distinctively…And I’m not a movie buff by any stretch of the imagination. I mean, I appreciate action films as a fan, but I don’t have the repertoire to be able to articulate why it’s so great. But I just remember watching that movie and thinking that the fight scenes were so great.

There was one scene in particular where he’s being chased through the city in a car and the camera seems to move just seamlessly from inside of the car to outside of the car to alongside of the car. It’s as if every stunt man was passing a handheld camera back and forth during this action scene. I don’t know if you’ve seen it or not, but it was just so mind-blowing.

I actually rewound it and watched it again to see if I could see any cuts, and there were just none. From the moment he got in the car, all the way across the city, through gunfights and explosions and jumping and whatnot, the camera just moved in and out and behind and in front and there were no… I’m sure some of that was computer meshing of shots. But it was just such great angles that I thought that had to be the product of the director’s vision and probably from his stunt experience. Would you think so?

Ray Eddy: I totally agree. I believe I might’ve even seen one of the behind the scenes of how that scene you’re talking about was actually shot. And it was absolutely phenomenal and brilliant filmmaking and how you can make a continuous shot that goes for so long. The rehearsal behind that is unbelievable, to get it right as much as possible in that one take. And then as you said, you see most of it together, but it is phenomenal.

Often, stunt performers who move up in the ranks as it were in film and TV, maybe become stunt coordinators, and then can become a second unit director, which usually means you’re maybe in charge of directing the stunt scenes or some pickup shots and other things around. The film’s main director is doing the main action, but you know stunts and action, so you sort of direct, in a way, that particular scene.

So having someone who has that experience as a stunt performer and a stunt coordinator, and then a second unit director, to being a full director for a film like that, he’ll definitely — he or she — but in this case, he would definitely roll over their skills and experience to apply that to the whole film, and I think it adds a whole lot to it.

I would also say that of all the different types of stunts from car stuff to high falls to fire burns to whatever, fight scenes are my favorite. I think they’re the most interesting. I’ve done pretty extensive training in that and actually teach stage combat classes myself, too.

There’s a lot more to a fight than just throwing a punch. It’s really — and I’m not getting into it right now — it’s a whole different topic, but there’s an emotional component to a fight scene that I think a director like you’re talking about would have a better connection to maybe than a director who’s never been involved with action scenes intimately that way who’ll be able to draw a much more meaningful experience out of performers in a fight scene, even in a gunfight.

But definitely, in a hand-to-hand combat type of scene, there are so many more things, so many more layers you can get involved in that type of a scene if you really know what is going on in the mind of each of the combatants involved in the scene.

Dr. Gary Deel: And you held a stunt management position at Walt Disney World as part of your senior years there. And so was that similar in capacity where you were choreographing the scenes and giving some vision to it, as opposed to just taking instruction on “here’s where you’re going to take a punch or throw a punch,” et cetera?

Ray Eddy: Actually, the role, again, theme park versus film, they’re pretty different, unfortunately. So that stunt manager was not really the same as a stunt coordinator because my job in that position at the “Lights, Motors, Action,” the cars/motorcycle show, was more during the scene that’s happening live.

I was on a radio communicating with all the performers, giving them verbal cues when to start and stop. Whenever something might go wrong, I would have to stop the scene, emergency stop the whole scene. You’ll yell the word…not yell, but you urgently say the word “abort” really fast to make sure everyone knows to slam the brakes on or someone’s going to get hurt.

So it was more of a safety role. It was cues to make a good-looking scene, but also safety to make sure that no one does something wrong and end up in the wrong place and maybe drove a car into a motorcycle then someone really gets seriously injured.

So it was a lot less of directing and choreographing and designing, as much as just running it because it was the same thing every single day. It was already written and choreographed and rehearsed. I just came in to run it. So it was [a] much simpler job than coming from scratch.

Dr. Gary Deel: Gotcha. Okay, I understand now. Now, you have an independent film company. Could you tell us about that? And did your stunt career inform anything with regard to the work that you do as a part of that enterprise?

Ray Eddy: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I honestly started that because if you go back to my earlier comments about “Do I want to move to L.A. or not?”

And the feeling was no. One of the main deciding factors in staying in Orlando was rather than go somewhere else and try to get work in someone else’s movie, “Why don’t I just make my own and I can do whatever I want?”

It’s never quite the same. I’m not going to have a multi-million-dollar budget rolling in, knocking on my door, but you can find some money or you can do things on the cheap, or you just take more time and ask for favors. But you can write whatever movie you want to do and just do it yourself.

The technology has gotten so accessible now that, with a few buddies and a phone, you can go out and you can shoot something crappy that’s not going to be in theaters, but you can go out and make movies. But then you find more people in the industry and people with connections and knowledge and skills

And I’ve found some wonderful, wonderful colleagues I just really adore who I love working with whenever I can. You get the team together and you get a vision and an idea, and then you flesh out a script and then you pick some days and do some casting and ask some friends for favors and find a location where you don’t need a permit, someone’s yard, and you go out and shoot some stuff.

Of course, because of my background and my desire to be involved in action type of sequences, the films that I have worked on and like to work on typically are action-oriented type of things. So if I had the opportunity to make more, I certainly have script ideas. Everyone in the industry does. Everyone wants to be a director probably, but I was able to do some directing and some producing.

And then of course I was also in them, so I’d have someone else come in. I wasn’t arrogant enough to direct myself. I can’t be Clint Eastwood who can do that, but I could direct the film and someone else would direct me, my second unit director, and then I get to do whatever I want.

So I can do fight scenes and I can do sword fighting and I can do action and whatever type of character is interesting and fun to me. So that’s really the desire, I think of…The motivation for starting a film company for me was I want to make the things that I want to make, and that’s what I focused on.

Dr. Gary Deel: Absolutely. Can you tell us about any of your recent projects or work that you’ve produced so far, anything that you’re particularly proud of?

Ray Eddy: Let’s see. I’ll be very honest with you. As you mentioned earlier, I’m working on a Ph.D. right now, so that has put a hiatus on everything.

Dr. Gary Deel: Sure.

Ray Eddy: In the last couple of years, I’ve been completely overwhelmed with coursework and writing and my comprehensive exams. My first one is tomorrow, so this is a great study break. I’ll do my summer dissertation in a few months and then have that done hopefully within a year.

And so that will free up a little more of my time to get back into it. So it’s been a couple of years since I’ve done anything, I’ll be very right off the bat with that.

But the biggest project I did, I was working on a film with someone else. I was cast in a film, and long story short, it led to us working on another project, and then that person pulled away from the project and I took it over and finished it myself.

So I ended up with a feature film that’s a horror film. The title we wanted for it was called “The Lost Coven.” I ended up finding a distributor for it.

The pride I have in that project is the fact that it got finished, which apparently as I’ve learned in retrospect is kind of rare. Most films never get done in the first place. Next is that I actually found a distributor, so a company that would take it around and try to sell it.

And then step three is they sell it, whether it sells to a foreign distribution area or it comes to HBO or whatever, or a Netflix or something. The market is changing rapidly and dynamically constantly, but this was, I guess, maybe five, six years ago.

And so I got it done, which was great, got a distributor, that was great. They took it all over to sell it, all at different film festivals all over the world.

The problem with the film, I’m not trying to say it was a great film, it was certainly a B, a C film, but we didn’t have anybody famous in it. That was the one criteria that was mandatory for any kind of a sale.

If you’re going to make a film with Paramount or Universal Studios or somewhere big — Sony — you’re going to have big budgets and big money, and you’re going to get a sale. If you’re a small independent company, you have to at least have a famous person in it. It doesn’t have to be Tom Cruise. It could be a person who’s been on CSI 15 times and that they recognize their face on the cover of your advertising, but we didn’t have anybody.

I’m certainly not famous. I’m not even famous in Orlando, and I played Indiana Jones. No one knows who I am and that’s fine, but we didn’t have any name actors who could help us sell it. Their name could help us sell it. So it never got sold. That’s part of how the business works.

So I now have possession of it again. I now own the rights to it. I’d love to think that someday an opportunity might arise where I could get it out.

I could just dump it on YouTube and show it to people, but I’d rather actually get some distribution for it and get some legs out if I could. That may never happen, but I’m hoping that maybe someday it’ll be worked into some other project or some other reason, or heaven forbid, someone in the film gets famous doing something else, and then I can ride their coattails.

That was the biggest one. It was a lot of fun as a project. The distributor who I got changed the title unfortunately. They changed it to “Island of Witches,” which I think is a horrible title. I’m not going to blame that on why it didn’t sell, but I never really liked that title. So anyway, that’s kind of where it is now.

Besides that, what we have right now, now that I’m kind of getting back into the real world of communication with my production team, we have a few projects, mostly short films we’d like to work on. We have two or three that are kind of in the works. Some are pretty simple, some are more complex, and those are the projects that we’re trying to move forward on.

It’s not like they tend to make a lot of money, but we’re not doing it to get rich. We’re just doing it to make fun projects and hopefully get our work out in front of people and enjoy the process.

So that’s kind of the short version of where things are. I’d love to think I had more things on the resume that I produced, but it’s really the one big one, and then just little things here and there.

Dr. Gary Deel: Well, it sounds like you’re doing what you love, and that’s important. It’s great that the technology to your point earlier has allowed folks that might not have access to the Industrial Light and Magic of Lucas Arts to do the things that they’re doing with “Star Wars” and with the Marvel series, and so on and so forth.

But today, I’m impressed when I go on Zoom and I can use a greenscreen background, even though I’m not sitting in front of a green backdrop and it still can tell where my body starts and the backdrop begins. So the software that’s available to the general public is getting more and more impressive.

Well, so all things considered, to wrap us up, I guess my last question would be, is the career path that you followed in stunts and entertainment something you would recommend for young professionals who might be listening to this and thinking that they have a passion for the same thing? If yes, do you have any advice for those folks in terms of following the same path you did, or to take a different direction?

Ray Eddy: Sure. I’ve had a number of people come talk to me about how to get a career in stunts. My biggest advice to them is, first, make your decision about do you want to do the theme park route or the film route? And they’re not mutually exclusive, but where is your energy going to go?

Because if you want to do it in films and TV, you probably want to move to, honestly, Atlanta right now is the biggest place to go where it’s not quite as insane as Los Angeles. I know there’s a ton of production in Atlanta. Also, New York or you go to Chicago or Louisiana has some…They’re hotbeds of production as well, but it takes moving there.

That approach to the industry is, I would say, I have not done it myself, but from what I’ve heard from people who have, it’s way more about how you network than about necessarily your skill set. You need to have both.

But you can be the most talented stunt person on the planet, and if you don’t network and meet the right people and have them decide they like you and they want to bring you on their team to work on their film, you’ll never work.

They don’t even have auditions that often for stunts, it’s more the director hires a stunt coordinator or the producer hires a stunt coordinator, and that stunt coordinator brings their team, people they always work with and they help each other out on different films. So they might have their team of eight or 10 or 15 people they always use.

Cracking into that team of 15 people is really, really difficult and it can take years, and it might never happen. Or you might get lucky and get on your first film, and good for you. But it’s much more about networking, meeting people, shaking hands, take someone out for a beer and talk about the industry and try to make friends without being a complete sycophant versus the theme park version, which is train and try to get the skills you need and go to auditions, which they have at least once a year, if not twice.

Currently, with the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s not much going on for shows or auditions. But in a normal time, they happen regularly, and you can audition for shows at a number of parks in Orlando, obviously, or parks around the world.

And you can find a job and you can have it and do stunts five days a week, all year long, and have a great time being a stunt performer. It’s a different kind of life. You’re never going to make the potential tons of money you could make in film and TV, but on the flip side, less chance of not having work for six months. So it’s a real balancing act.

So that’s kind of the first choice is that, but in either route, it’s very important that you, first of all, are great to work with. You need to not be a pain in the butt on the set or in the green room. It’s a lot about how you work with people, how hard you work, how fun you are to be around, what kind of a good attitude you have on the sets or at the park, and you have to have the skills. If you don’t have those skills, most people can train and get those skills.

I always recommend gymnastics, back to your first point. Gymnastics is the number one I think physical activity you can do to make you feel more ready and maybe be more qualified to be able to do something in stunts, because so much of it is just physical.

Rolling down a flight of stairs, if you can find yourself in the air as you’re hitting the ground over and over again, it’s way easier than if you just kind of roll down the thing and hope you land right without breaking your neck. But then martial arts, and there are stunt schools you can go to learn some basic skills about air rams and learn some basic car stunts and how fire stunts work and how camera angles work and wire work, that kind of thing.

So there are all kinds of things that you can definitely do to prepare yourself by gaining skills. But it usually takes a real dedication and the ability to sustain yourself as you’re pursuing the job, because you don’t normally get it right away. So it’s a bit of a long-term process.

Dr. Gary Deel: Absolutely. Well, thank you for sharing your expertise and perspectives on these topics, and thanks for joining me today for this episode of Intellectible.

Ray Eddy: It was my pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Dr. Gary Deel: Perfect. And thank you to our listeners for joining us. You can learn more about these topics and more by visiting the various APUS-sponsored blogs. Be well, everyone, and stay safe.

About the Speakers

Dr. Gary Deel is a Faculty Director with the School of Business at American Public University. He holds a J.D. in Law and a Ph.D. in Hospitality/Business Management. Gary teaches human resources and employment law classes for American Public University, the University of Central Florida, Colorado State University and others.

Ray Eddy holds a bachelor’s degree in mathematics and economics and a master’s degree in teaching from Duke University. After earning his degrees, Ray decided to pursue his true passion of being a stuntman. He has worked in the entertainment industry for more than 20 years.

He held a role at Walt Disney World, playing Indiana Jones in the “Indiana Jones Epic Stunt Spectacular.” This led to an active career as a full-time actor and stunt performer, including numerous additional acting and stunt acting roles at Disney World and Universal Studios, as well as work in commercials, television, and film.

During Ray’s tenure at Walt Disney World, his management experience was recognized, and he moved from primarily acting and performing stunts to becoming a stunt manager and entertainment manager. He worked with numerous complex shows in various areas of the theme park for several years. His most recent management role was with the “Lights, Motors, Action Extreme Stunt Show,” which closed in 2016.

Along with his stunt, acting, and theme park experience, Ray also created Lost Coven Films and has produced, directed, written, and performed in numerous works, including a full-length feature film that received multiple offers from distribution companies. Prior to his entertainment career he also created – and for 20 years ran – a company that provided music camp experiences for students across the country. Ray is currently a full-time instructor at University of Central Florida’s Rosen College, teaching in the entertainment management program.

Comments are closed.