Perhaps the most important question to ask after completing a project at work is “So what exactly did we learn from this project?”, “How can we achieve better performance in our next project?” or other similar questions. If you are like many project leads and team members, the answer to those questions might be focused around learning what not to do during your next project, such as in preparing a better budget or in making more accurate activity estimates.

Regardless of the questions you ask yourself about your last project, there is a better approach to finding the answers. Ideally, start at the very beginning of your next project and do not wait until it ends to ask these questions.

Pre-Project Actions

It is vital to understand that proper project management starts before your next project. These five tips will help you get started on learning lessons from your projects:

1. During the project planning phase, be sure to do your homework. Has the company done any projects in the past that have provided valuable project management lessons? What were the results of that project? Are some team members still around from a similar project in the past to provide their wisdom?

2. Before beginning to write the project charter, focus on the specific objectives for the project. That’s your baseline of consideration. Remember that both you and your client have specific objectives in mind, so you’ll need to consider them in an objective, measurable manner.

3. Know your scope-time-cost baseline from the initial phase thoroughly, and be prepared to update those baselines if changes are sought and approved. At the same time, retain your awareness of the original baseline.

It is essential to consider the project sign-off by the client upfront. The client will review the performance criteria for the project’s work, so that ensure that each project element is clear and measurable.

4. Know the company assets that will be available during the project. Understand the specific resources, constraints, limitations and risks from the project’s start. Your available company assets will have a profound effect on how you write your project plan.

After the project is done, some people may ask, “Did we use our resources well during this project?”, so understanding available company assets is critical. The concepts of constraints and resources are related to your project’s risks, and they will be taken into consideration later. Ask yourself, “If any of the risks identified in the original planning actually occurred, to what degree did that impact project planning and results?”

5. Consider that changes to projects often happen. During the project execution phase, be sure to understand what unplanned events and issues arose during the project and how those unplanned events impacted your baseline.

Start compiling a list of significant events that occur during your project as soon as those events start. This list will serve as useful input later when you’re determining what lessons were learned from the project. Start with identifying the event, but keep in mind that you may not understand the full impact of that event until later on in the project.

With these five tips firmly in mind before the project begins, you will have a firm footing on which to build your post-project lessons learned. The project lead’s work really begins with the normal updating of the project.

For instance, if a cost overrun on materials occurred during a specific task, the reason behind that overrun must be noted and how it impacted the project’s overall costs. Many modern project management software programs allow for the project lead to update baselines to projects, so this work will help greatly in properly managing the project. However, the original baseline must be retained as a reference point.

Two Levels of Review Are Needed for Learning Lessons from Recent Projects

In learning lessons from a recent project, there should be at least two levels of review. First, consider how the project did within its bounds, which are the internal dimensions of the project’s metrics. In other words, considering the internal metrics of the scope-time-cost triad, how did the actual results vary from the planned results?

Second, the project needs to be reviewed in context to the company’s strategy, which are the external dimensions of the project’s metrics. For instance, although the internal performance metrics of the project may not have been stellar, perhaps this project was the first of its kind for the company and opens up another whole customer segment for the company to pursue.

So even though the internal metrics weren’t exceptional for that project, the fact that it was even marginally successful for a brand-new market segment or even a potentially huge new customer could be of critical importance to the company on a strategic level.

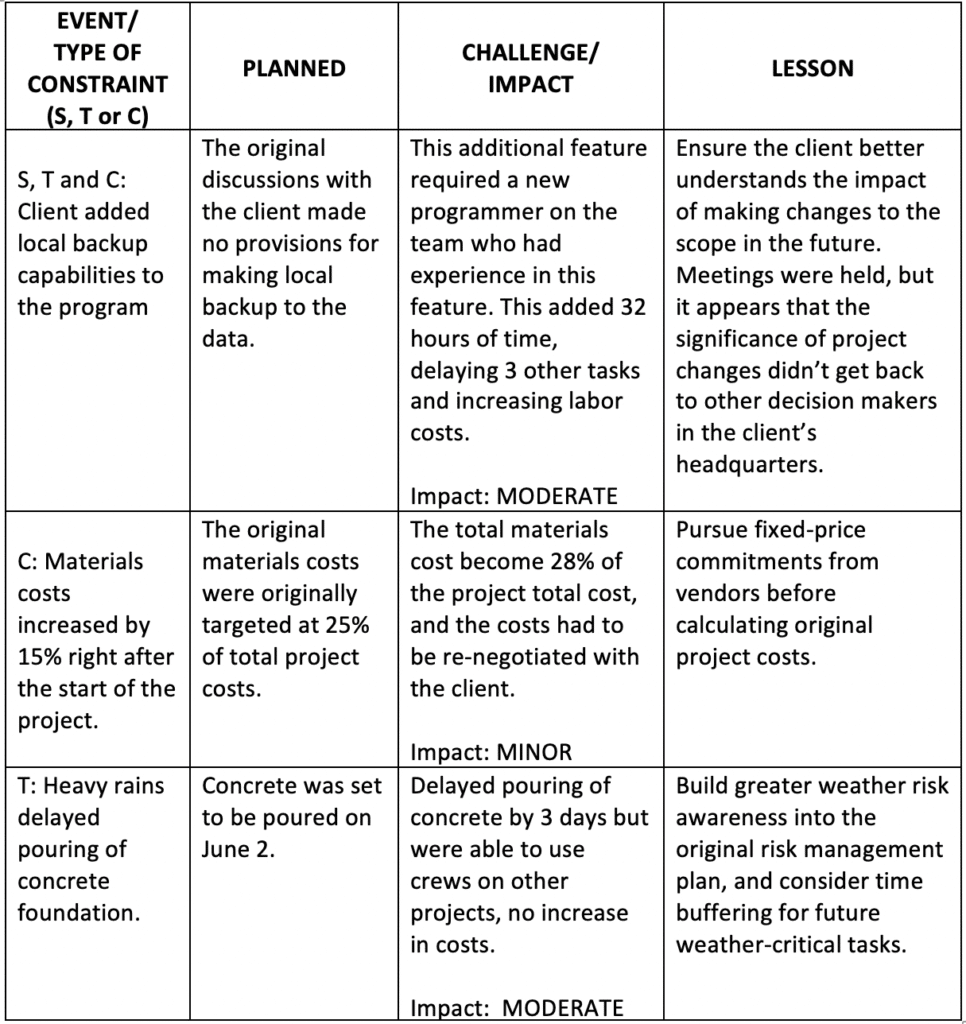

With these two levels of review in mind, then the three fundamental constraints to all projects – the scope-time-cost triad – must then be individually considered. A basic worksheet such as the one depicted below can be used to document your results during the project. As you fill in this worksheet, remember to consider both internal and external project metrics.

Example of a Project’s Lessons Learned Worksheet

Type of Constraint: S=Scope, C=Cost, T=Time

Post-Project Actions

After a project is completed and signed off by the client, the lessons learned process can begin. As with any effort, be sure that the right people are in the room before the post-project analysis meeting begins. For most large projects, there are team members from each of the major functional areas in the company so these same representatives should be in the room for that meeting.

Depending on the nature of the project and your relationship with the client, the client’s feedback should be sought and a separate meeting just for the client may be in order. It may result in a more candid assessment by the client when individual project team members are not in the room.

How to Structure the Lessons Learned Conversation

To start off the meeting, the key objectives of the project should be restated by the project lead in order to remind everyone of the project’s baseline. The meeting could then feature a graphical representation of the project’s work breakdown structure, using information collected from the lessons learned worksheet.

Using this structured approach to a lessons learned project management meeting, it is more likely that tasks and problems will not be overlooked by team members, especially those tasks and problems that may have occurred at the project’s beginning and have been out of everyone’s consciousness for some time.

In conclusion, a viable lessons learned protocol for your projects can help develop your project team members by helping them to be better prepared to work in future projects. This education adds to team members’ skill set but also provides a project lead with a more solid foundation for success in his or her next project.

By taking these steps in your project management work, you are reinforcing the culture of a learning organization, as championed by writers such as organizational learning expert Peter Senge. This learning aspect will extend outside the realms of a company’s projects.

This approach enables a project lead to fully develop team members, so they will be an even more valuable asset to the organization as a whole. The improvement of team members will also be helpful to their supervisors when those team members are released from the project and return to their normal duties.

Related link: Project management courses are available as a concentration in our online bachelor of business administration and online master of business administration programs.

Comments are closed.